Original "Boys in the Band" Star Laurence Luckinbill: "The New Show Has Something We Didn't Have"

Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band—the 1968 play which became a 1970 movie—is a seminal work about gay camaraderie and bitchery that’s currently playing out a successful run on Broadway. Jim Parsons, Matt Bomer, Andrew Rannells, Zachary Quinto, and Robin De Jesus are among the gay all-stars who make the play crackle as a still relevant period piece about angst under oppression.

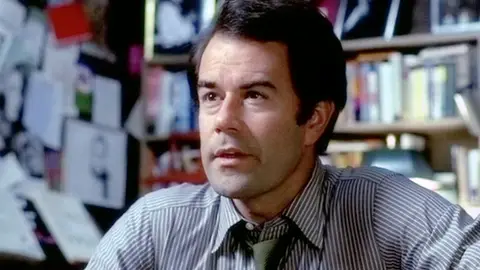

One of the few people from the original production who is still alive, Laurence Luckinbill, played Hank, who was married to a woman, but now wants a monogamous relationship with the younger, friskier Larry. (In the current production, Tuc Watkins plays Hank and Rannells is Larry.) Laurence was Hank in the original workshop, then the off-Broadway production, and then the London company, followed by the shooting of the film in New York City. Married to Lucie Arnaz (famed daughter of late comedy legend Lucille Ball), the expert actor agreed to take a look back with me on what made Boys in the Band so groundbreakingly special.

Hi, Laurence. How did you feel watching the new Boys in the Band?

I saw it at the special opening night. It’s like almost 50 years have gone by since I saw Peter White [who played the closet-y Alan in the original]. We picked up our same relationship. “What’s wrong with you, Peter?” [laughs] I thought the production was absolutely splendid. [Director] Joe Mantello is such a marvel. I grabbed him after. We went to Second Floor, a party place. I said, “The Playbill makes you look like an Italian bricklayer, and you are. What you do is lay the bricks for a very solid foundation for the first 45 seconds of a play. It’s stunning that you’ve learned to do this.”

Lucie and I saw Three Tall Women the day before. I detected Joe’s sure sense of event in both of these. I was blown away. However, on a month’s reflection, I see something else in these new guys that I don’t think we had in our show. There is a freedom that has been given by circumstance and society to be gay and out in certain sections of the world, like New York. The freedom to be who you are, I think, imbues these new young actors because they have come out before this and I think that gave them the right to be even crueler, in a funny way. The hostility is really present throughout the production. There’s somehow less fun and more war.

Things were wildly different back then, of course.

We did not know what we were doing because nobody was out. There were two in the cast that were straight—Cliff Gorman [who played Emory] and me—and seven that were not. Everyone was telling us, “It’ll wreck your life.” I don’t know what the agents were telling the gay people. I think those seven who came out as a result of the play because they admitted who they were in the play had a much braver, tougher time than either Cliff or [me]. I am very sure of who I am. I was worried that I was gonna get typed. And I think Cliff smoked a lot of cigars in public after that.

The cast of Boys in the Band (1970).

Was he tortured about the ramifications of playing such a flamboyant queen?

No. I don’t think so. Cliff was a tough guy.

He was brilliant in the role.

He was. So is Robin De Jesus. He’s brilliant in a different way—in a more settled, “I know who I am” way. Cliff was working on “I don’t know who I am. Why do I have to be this way?” Mart’s thing in his whole life is, “Why do I have to be gay?” He did not want to be gay. Being Roman Catholic exacerbated it. To me, the play was so shocking at the time. It was the turning of the ignition key for the gay liberation movement, and Stonewall provided the spark a year later. What happened at the workshop was so extraordinary. The first night, we were stepping on each other’s lines, and everybody was unsure of who we were. We were supposed to have known each other a long time, but we had just met the week before. We were hanging onto each other like soldiers in a battle where you stay with your buddy in order to stay alive. All nine of us were like, “What the fuck is coming next?” It was coming so fast. When we worked on it, I remember feeling how long the play was, but Bob Moore was a directorial genius like Mantello. He had a marvelous sense of humor. If you threw a tantrum, you were sure to feel a whiplash sting from something Bob would say in the sudden silence. You did not do any tantrums after that because everybody laughed at you. One actor could not get ahold of his role. He kept being hostile toward it. He was replaced. Look what he lost.

Leonard Frey was unforgettable as the lacerating, self-deprecating, slithery Harold.

There was nobody better, and even Zachary [Quinto] isn’t quite it. He’s good. Leonard had something else. I’m not here to criticize this cast. I think they were splendid. I watched it knowing where every line was coming and where the cuts were, but that did not impinge on my enjoyment of it at all. I was really with it, with Andrew Rannells and Tuc Watkins when they were struggling with their lives. I loved Matt Bomer’s Donald. He did a splendid job. But Frederick Combs was Donald. It was the difference of a cast who knew and lived being in the closet, being locked in. They felt surrounded by danger because it was real. With the new freedom to say who you are, which doesn’t extend much farther than the Eastern and Western coasts...not Montana, which is still a dangerous place to be gay. I wonder what all the fuss is about sometimes. [He reads from his upcoming memoir] “It seems so easy to love one another, if only the divisions were dissolved…”

Your memoir sounds great. Let’s go back to the beginning. You knew Mart Crowley from college?

Yes. Catholic University of America in D.C. He was in the undergraduate theater department and I was in the graduate theater department. I’d been in the army. Mart was from Mississippi and I was from Arkansas, so we understood a lot about each other just from that. The Catholic University drama department was divided into two sections—the lab theater and the main theater, an ex-army post-theater, which was beautifully done, wooden, and with great acoustics. The people that worked in the main stage were gonna be the stars and the people that liked the lab stuff were not; they were the other people.

I met Mart at the lab—we were drawn to it—and we became friends. One summer, he called me and said, “Can I come visit you?” He was in Mississippi. His parents were fighting terribly. They were both addicts of varying kinds. He came to visit me and we had the most personal talks we’ve ever had about what life was all about. Ten years later, he called me in New York and said, “I have this play. Can I come and bring it to you?” I said “Yes.” We met at Jack Delaney’s in Sheridan Square. I took it home and read it. We met again and he said he’d had terrible trouble getting people to read it. They didn’t want to be associated with it. It was like a verboten piece of poison. All of that affected me. It was quite moving because I knew what he was all about. Back then, there were circles of boys that were oddballs, sort of odd men out, and nobody talked much about what gay was. There was no such word. There was “queer” and “faggot” and those kind of things. I knew he was part of that group. Quite a few of them ended up participating in the production of Boys in the Band. We met again and I told him straight off that I would do the play, and he was very grateful. We did a five-show workshop production at the Vandam Theater.

Were you the first actor to agree to do the play?

I think I was.

Did you feel any nervousness or trepidation about doing it?

I really didn’t. The honest reason is he was my friend and that took precedence to me. I thought it was a good play, I thought it was fun. It’s what we in those days pejoratively called a well-made play. A lot of it was awe-ful in the real sense of filled with awe, that people could behave this way, that people could behave this deeply. It was so out front that it was shocking. It wasn’t just the gay stuff, it was that anybody took love this seriously. We were used to [actor] Barry Nelson sitting on a couch and talking to [costar] Barbara Bel Geddes. Everything was light and fluffy on Broadway. Put your knees together, you’re very graceful, and all of that. Here’s this bunch of guys tearing into each other and yet the friendship is eternally underneath, like a river, like Ol’ Man River.

From left: Laurence Luckinbill and Peter White in Boys in the Band (1970).

The most affecting line for me is when Harold says at the very end, “Call you tomorrow." Okay, this is a permanent condition that these men live in, and none of us knew that, but I learned it by getting to meet the cast. By this point, I had a Drama Critics Circle award, I was doing well and was quite respected because I did a lot of Shakespeare and all the classics at the McCarter Theater in Princeton. All those directors knew me. I was doing really big parts, but I was making zip—$100 or $125 dollars a week. The biggest luck I had was getting a soap opera on CBS, Secret Storm. It was a wonderful part. I was not in any need to do that play and it was for nothing anyway. None of us got paid. It was a little tiny closet of a theater—somewhere between 50 and 100 sets. There was no publicity and no reviews because Eddie Albee did not have any of his playwrights unit productions reviewed. So if it died, Mart was headed back to Hollywood to be a maid of all work to Diana Lynn and Natalie Wood. He was a personal secretary.

So people warned you not to do Boys in the Band?

Yes. People told me I was going to lose my career. The doomsayers included my agent, who was a gay woman married to a gay man. But she said, “You can do it, but you’re throwing your career away.” I said, “But you’re representing the play.” She said, “That’s very different.” I understood that it was. She was trying to protect me because she thought it would wreck my career.

Did it end up hurting it?

I lost a couple of commercials. It was a True cigarette commercial. I was a huge face on the TV screen and I had a cigarette. I blew the smoke out toward the camera and said some innocuous line, “You’re really gonna enjoy this.” You know, “Smoking is good.” I think it ran for three cycles, meaning 39 weeks. I was making a lot of money from it. I got a call from Richard, the casting director, who was gay, a very lovely guy. I go up there. The play had been running for three or four weeks. There were six clients sitting there in their suits and ties, all smoking. I said, “Is it a requirement?” I read the copy for them and they said, “Thank you very much.” I left and was heading toward Grand Central. Richard’s secretary came down and grabbed me and said, “He needs to see you.” I went back and Richard said, “Well, Larry, I don’t know how to tell you this. It’s bad news. They don’t want to renew your contract.” I said, “Why? Was it something I said?” He said, “No. The only thing the head guy said is, ‘No fags smoke our fags.'” I said, “Who wrote that copy?” He said, “I’m so sorry.” I said, “You know how it is with commercials. It’s just good money. I love doing them and am good at it. I don’t mourn over losing one, I’m just sorry over the kind of thinking that...” He said, “Yes, I know.” I knew I was talking to a closeted man and those days you respected that. Also, nobody kosher would have outed anybody because it was life and death in some cases.

Laurence Luckinbill today.

You lost a commercial just for playing a gay.

And what short-sighted shit is that, because who in America seeing an anonymous face would say, “He must be gay. He was in that play”? Please. But that was their fear coming to the fore in a particularly nasty way. They made a joke about it, and Richard was offended by that joke.

On a brighter note: Your parents saw you in the show?

Yes. I was a stage carpenter at Catholic University to pay my way. I had a nice tool kit. Peter Harvey was the designer. He went to Bloomingdales and photographed the men’s department. They blew the photos up and put them on boards and turned it into the surround of the set. It was the set. It was as if [the character] Michael had hijacked his set directly out of the men’s department of Bloomingdales. I had drilled holes so you could see who was sitting in the audience. One night, I looked and saw my parents sitting there. Emory said, “Who do you have to fuck to get a drink around here?” I watched my parents. They were like [makes unhappy noise]. And yet, I detected a hint of humor in them—that they were shocked, but they also wanted to laugh.

After the show, we were walking to Ralph’s restaurant and they said nothing at all. I finally said, “Hey, what’d you think?” My mother said, “Well, it was interesting.” My father was looking off, like a thousand yard stare. He said, “When I was 21, I worked for the American Express company and was the sole operator for the night shift. I was young and strong and remember the freight trains would come in and I’d have to take the freight train by myself. I wanted a better job. I had this friend who got to go to work in a suit and tie. I admired him. He was an executive at a bank. We’d go for walks along the Arkansas River. One day, he gave me a book of poetry. When I read it, I didn’t know what to think or what to do. I gave it back to him. I believe that fellow was homosexual.” And I said, “Yes, and what happened? Did you end the friendship?” My father looked at me like, “What are you talking about?” He said, “No. He was my best friend.”

The cast of Boys in the Band (1970).

Seeing the play brought that out in him.

Yes, it brought out that memory. If you’d asked him before that, “Do you know any homosexuals?”, he’d have said “No.” My mother would have said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” People learn at their own pace, if they’re willing to learn. I realized they were far greater people than I’d imagined.

I’d love to read that poetry book! Let’s talk about your character, Hank. I think the nervous Alan is drawn to him because Hank seems the butchest of the bunch.

Absolutely. That’s one of the most slightly eye-stretching moments when he says, “Hank, let’s get out of here together.” That seems a little weird to me. Alan is kind of underwritten and maybe Hank is too. But I think Hank sits exactly where he should. Once I committed to the part, I thought, “He’s a square, he gives people cardigan sweaters as a gift, what’s in this part?” So I just did me. I just did what I do. I was studying with Uta Hagen and she was tough, as you know. One day I was doing a scene. She stopped me and said, “You know...”—smoking a cigarette and blowing smoke away from your face—“you’ve got technique, that’s indisputable. Now go find yourself.” It was an eye-opener. I think by time Boys in the Band came along, I was on the path of finding myself in a part. I know that’s what ultimately makes a star—they do all kinds of different things, but there’s this powerful self that always comes through. Not that I’m comparing myself to big stars, but had I stuck with that, I would have been better served.

You didn’t stick to bringing yourself to the material?

Some of the television things, there was nothing I could grab onto. I didn’t realize you could insist. David Susskind, who I called my Dutch uncle, he’d send me a piece of work, some series or sitcom. I turned it down three times. Every time, he would say, Why?” I said, “It’s a piece of shit, David.” He said, “You’re unemployed, aren’t you?” That worked on me. I came from blue-collar people who never believed I could make a living from acting. They finally had to believe it. They were very nice people, but they were fearful.

The cast of Boys in the Band (1970).

Did you talk to Tuc Watkins about the role?

Tuc and I had lots of good conversations. He said it hasn’t changed all that much. He told me, “When I came out about three years ago, I stopped getting work.” He said he had to move back to the Midwest to get work again.

That’s awful. Mart Crowley told me he feels Tuc looks eerily like a young you.

He actually does. And Lucie said that. “My God, he’s a ringer.” The way he sat and comported himself onstage!