The Fountainheads: Alain Locke, Father of the Harlem Renaissance

This is a weekly series during LGBTQ History Month profiling queer people who have inspired styles, opinions, and entire movements.

"We're going to let our children know that the only philosophers that lived were not Plato and Aristotle, but W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke came through the universe." — Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1968

What is the role of art in society, and the role of the artist? Storyteller? Philosopher? Revolutionary? Some consider art mere decoration, while others view it as an essential component of life, like the air to feed our lungs and the water to sate our thirst. For famed scholar Alain Locke, the arts were the key to the self-actualization of the black race.

The first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke mentored and facilitated the work of some of the brightest luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance. Though he yearned for some of these relationships to turn romantic—particularly with Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen—his love remained unrequited.

Alain Leroy Locke was born into a middle class, black Victorian home in Philadelphia, Penn. on September 13, 1885. His father Pliny was the first African-American employee of the U.S. Postal Service and his mother Mary was a schoolteacher. After Pliny died in 1892, Alain and Mary grew inseparable and would remain so until her death in 1922, from which Alain never truly recovered. To wit, at her wake, the devoted son had his mother’s lifeless body propped up on the couch in the parlor to receive guests. That may sound like some serious “A boy’s best friend is his mother” shit, but Norman Bates was misunderstood, too.

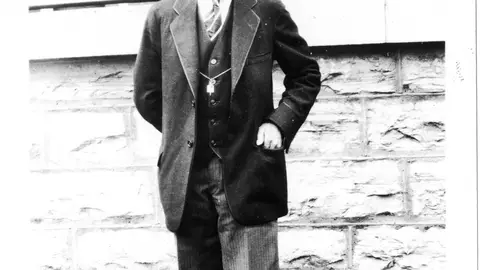

Sickly as a child and diminutive as an adult—he barely stood five feet—Locke found refuge in his studies, and Mary indulged her son’s every whim. Their dedication paid off in 1907 when Locke graduated from Harvard University, at a time when less than 1% of the prestigious Ivy League’s students were black, and was subsequently named a Rhodes Scholar. At Harvard, Locke distanced himself from his fellow black classmates, the handful of them, writing to Mary that they weren’t “gentlemen” as he saw himself or at least aspired to be.

Locke instead found kinship among a cadre of homosexual white classmates, bonded by their love of aesthetics. He was particularly fond of fellow Philadelphian Charles Dickerman, for whom he feigned an interest in Celtic literature as a prelude to pitching woo. Whereas Locke excelled at Harvard, he languished on the vine at Oxford, his time there hampered by literal institutional racism—he was denied admission to several colleges—and was made a pariah by white American Rhodes Scholars from the South. Fun fact: racism is still one of America’s greatest natural resources and biggest exports. Still, that didn’t keep Locke down, and he eventually attended Hertford College, though he didn’t claim an Oxford degree, and later the University of Berlin, where he at least got to claim some sexual conquests.

The German capital's lax laws regarding homosexuality attracted any number of gorgeous youths, and Locke was excited to sew his proverbial oats, though he was disappointed to find that he didn't have the coins to afford the city's rough trade. One friend, Von Voss, a German he met at Oxford, wrote to Locke in the spring of 1911 inquiring about the "fee of a nice looking boy in Berlin" around age 16 or 17. Locke, ever the gentleman, was not amused by the boldness of Voss, who was apparently running short on both funds and fucks when he wrote a broke Locke, "You are only a sir if you got money? Everybody want money, money! I know it myself, but never mind. Cheer up! Don't be downhearted!"

Upon returning to the States, Locke landed a professorship at the historically black Howard University and went back to Harvard where he got his PhD in philosophy in 1918. Thereafter, Locke began contributing to the African-American papers of note, W.E.B. Du Bois’ Crisis and Charles Johnson’s Opportunity, putting him in contact with young writers. Using his position in academia, Locke found himself the bridge between these fiery youths and white patrons looking to throw money at them.

After his mother died in 1922, Locke decided to live his best life, which is probably why he ended up in Paris at Langston Hughes’ door in the summer of 1924. As Hughes later recounted in his memoir, The Big Sea, Locke, who was on vacation in Europe, had gotten his address from Crisis and decided to look up the 23-year-old poet. Locke immediately fell for Hughes, and hard, but as practically all of his infatuations would go, the attraction was not mutual. But Hughes, being a starving artist, milked the smitten professor’s ardor and his vast connections. Locke, a day after he had parted ways with Hughes, wrote him a letter eager for a day as perfect their last together so he could “tell you how much I love you.”

Inspired by his time with Langston Hughes, Locke penned the first draft of his essay, “The New Negro,” a treatise on the African-American identity that centered Harlem as the mecca of creation and expression. He would go on to expand on that essay, producing the 1925 anthology, The New Negro: An Interpretation, featuring some of the Harlem Renaissance’s most distinctive voices—Hughes, Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Jacob Lawrence, and Eric Walrond, among others—and helping to establish many of their careers.

Hughes and Cullen, however, proved elusive, choosing to conceal their lives as gay men and distancing themselves from Locke, who was, more or less, in a glass closet. As Jeffrey C. Stewart notes in his recent biography of Locke—also titled The New Negro—“To become closer to Locke would have made Hughes homosexual by association.”

Cullen chose the time-honored tradition of the closeted gay and entered into a “marriage of convenience” with W.E.B. Du Bois’ daughter Yolanda. Their wedding was a grand spectacle with more than 1,300 guests, Yolanda had 16 bridesmaids, and at one point Daddy DuBois even planned to literally release doves into the church. Locke was having none of it. He advised Cullen against the union, writing him, “I can forgive you for refusing my advice, but I cannot forgive you for transgressing a law of your own nature—because nature herself will not forgive you.”

Though often unlucky in love, Locke did have at least one long-term relationship, with one Maurice Russell, who was about 19 when Locke first met him in the early ’40s, and they dated on and off through the decade. Monogamy, however, was not Locke’s bag and he pursued other, younger men well into his twilight years. While still with Russell, Locke set his sights on a young man by the name of Robert E. Claybrooks, who was excited by Locke in “every other area but a sexual one” and, adding insult to injury, wrote the older man claiming initial physical contact with him caused Claybrooks “an intense feeling of nausea” that “I know it would be repeated each time, if such were to happen again.” Yikes.

From the vantage point of the #MeToo era, Locke comes off as predatory, leveraging his status as both mentor and a cultural attaché of sorts to curry sexual favors with his young protégés, but I guess that stuff flew between closeted/quasi-closeted homosexuals in the early 20th century navigating a tricky and potentially perilous racial and sexual landscape. Another fun fact: Locke also kept vials of his ex-lovers’ semen. Because I guess that also flew back then. Just because he was an intellectual born of Victorian mores and attitudes doesn't mean Alain Locke didn't likes to have some funs.

Locke’s contributions to African-American, and thus American culture, went largely overlooked following his death in 1954, but Stewart’s 900-page biography published earlier this year pulls back the curtain on his fascinating life and life for black queer men at the turn of the century. Without Alain Locke, the Harlem Renaissance, and the men and women who defined it, may never have spread outside of the Manhattan neighborhood to influence generations of writers and artists and redefine the way black people were represented and represented themselves.