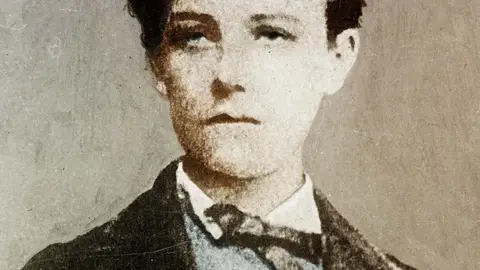

The Fountainheads: Arthur Rimbaud, Father of Surrealism

This is weekly series during LGBTQ History Month profiling queer people who have inspired styles, opinions, and entire movements.

What were you doing at age 17? Cavorting around with a man nearly twice your age, high on absinthe, opium, and hash, all the while churning out revolutionary work? No? Well what the hell were you doing with your life, sweetheart?

Arthur Rimbaud was a monumental but volatile talent who has intrigued generations of artists, rebels, and queers alike, from Patti Smith and Bob Dylan to Edmund White and Henry Miller. But then again, the idea of living fast, dying young, and fucking up the world while you’re here has always had a certain pull.

The second of five children, Rimbaud was born into meager means on October 20, 1854 in Charleville, France, to an absentee army father and a rather dour and taciturn mother. Though throughout his life he would often return to his mother’s aegis when the world became too much to bear, Rimbaud’s pet nickname for her was the charming bouche d'ombre, or “Mouth of Darkness.” Papa Rimbaud was constantly away on duty and when Arthur was five, he decided to stop coming home altogether—the abandonment characterized much of the poet’s work, and one could argue, the trajectory of his life.

Rimbaud’s brilliance was evident from an early age, as he greatly excelled in school and won numerous scholastic prizes. He published his first poem, “The Orphan’s New Year’s Gift”—about two kids awaking on January 1 to find their dead mother...you know, fun stuff—shortly after his 15th birthday. With the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) raging, Rimbaud grew restless to experience life outside of Charleville. The summer before his 16th birthday, he made the first of many escapes from his mother’s farm, landing in Paris via train. The rambunctious teen did not, however, have money for his ticket and was promptly jailed upon his arrival.

Instead of appealing to his mother, Rimbaud wrote to his favored and trusted teacher, Georges Izambard, who arranged to have the stowaway released into his care and Rimbaud regretfully returned home to mommie dark-mouthest. But the spirit of rebellion was now calling to him louder than before. He grew out his hair, started smoking a clay pipe, drank excessively, stole, openly insuled the folks in his town, and generally made himself a real pain in the derrière. This was all a part of his renewed dedication to poetry, as he wrote to Izambard in May 1871:

“I’m now making myself as scummy as I can. Why? I want to be a poet, and I’m working at turning myself into a Seer. You won’t understand any of this, and I’m almost incapable of explaining it to you.The idea is to reach the unknown by the derangement of all the senses. It involves enormous suffering, but one must be strong and be a born poet. And I’ve realized that I am a poet. It’s really not my fault.”

This sense of inevitability led the 16-year-old to write a letter, and enclose several of his poems, to noted French Symbolist, and one of the few poets Rimbaud actually admired, Paul Verlaine. He had reached out to other poets but Verlaine was the only one to reply—but what a reply. Verlaine, 10 years Rimbaud’s senior and married with a kid on the way, sent him a one-way ticket to Paris, with the note: “Come, dear great soul. We await you; we desire you.” From there, things quickly went off the rails.

Rimbaud descended like a hurricane into Verlaine’s life and home in late September 1871. Before you could say sacré bleu, the senior poet had left his pregnant, 17-year-old wife Mathilde for the fecund, 17-year-old enfant terrible, and they embarked on a two-year mission to scandalize major European cities, bouncing between Paris, London and Brussels, partaking in absinthe, hash, and opium, fighting and fucking in public, and playfully stabbing each other with knives.

Considered one of the most famous homosexual couples in history, some dismiss Rimbaud’s bizarre affections as part of his grand scheme of “derangement of the senses”—like memoirist and critic Daniel Mendelsohn in a 2011 New Yorker article on the bawdy bard:

Many readers and biographers see the couple as what one critic calls “the Adam and Eve of modern homosexuality,” but the evidence suggests that, as far as Rimbaud was interested in anyone other than himself, he was interested primarily in women. [...] It is hard to escape the feeling that Verlaine, an ugly man whose appearance Rimbaud made cruel jokes about, was a kind of science experiment for the poet, part of his program of “rational derangement of all the senses,” his strident adolescent ambition to “reinvent” love, society, poetry.

Scholars, critics, and historians have, historically, always tried to ruin anything gay for us, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that Rimbaud and Verlaine embarked on a very turbulent and very public love affair. While it might have been a one-time, two-year dalliance for Rimbaud, Verlaine would fall in love with another young, male mentee of his, Lucien Létinois. (Létinois died of typhus in 1883, by which point Rimbaud had given up writing and was living in Ethiopia.) As for Rimbaud and Verlaine, they met a less tragic, but ultimately appropriate, end.

Arthur Rimbaud in his Bed, Wounded by Verlaine in 1873 by Jef Rosman

After one of their trademark blow-ups, Verlaine ran back to his wife in Brussels, abandoning his 18-year-old lover in London, where they had been scraping by as French tutors for hire with the help of a literal allowance from Verlaine’s mother. Rimbaud, broke and alone, wrote his former and future lover, “Come back, come back, dear friend, only friend, come back. I promise to be good.” So it was no surprise when he took the lovesick Verlaine up on his offer to rejoin him in Brussels. But soon this prototypical-homosexual Liz and Dick realized their reunion was—much like the Lindsay Lohan Lifetime movie, Liz and Dick—a terrible idea.

They argued incessantly and Verlaine took to drinking and threatening suicide. On July 10, 1873, the sad-sack sonnetist bought a revolver, intending to kill himself, but he ended up shooting Rimbaud write, er, right where it hurts: in the left wrist. The tempestuous teen called the cops, Verlaine was sentenced to two years in prison, and Rimbaud ran back to his dark-mouthed mommy in Charleville.

Though literally and figuratively scarring, Rimbaud’s time with Verlaine also proved inspiring. On the mend at his mother’s farm, Rimbaud wrote “A Season in Hell,” a hallucinogenic and perplexing extended prose poem, evocative of his romance with Verlaine, that Mendelsohn calls a mix between Dante’s Inferno, Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground, with “a pinch of William Blake, and a healthy dash of Christopher Smart’s madhouse masterpiece Rejoice in the Lamb.”

“A Season in Hell” would go on to greatly influence Surrealist artists and poets, but upon its publication in the fall of 1873, it was met with derision and indifference. The petulant poet’s shenanigans with Verlaine, still fresh on the minds of the Parisienne literati, probably didn’t help matters either.

The reaction to what should have been his monumental work may have led to Rimbaud giving up writing altogether, but his legacy would be established with his final published work, Illuminations—a sprawling collection of 42 surrealistic poems written between 1872 and 1874 (or 1875). Rimbaud lived briefly with the French Symbolist poet (I guess he had a type after all) Germain Nouveau [sidebar: great future drag name...you’re welcome], during which he wrote new poems and revised old ones, some of them written during the happier moments of his tryst with Verlaine, that would comprise Illuminations. Verlaine and Rimbaud met up one last time in 1875, after the former had gotten out of jail for trying to shoot the latter—ah, l’amour—and gave his one-time mentor/lover his untitled manuscript, before embarking on a mission—perhaps not to find himself but lose himself—across Europe and Africa.

Verlaine, still oddly devoted to the boy and his talents, endeavored to publish the unfinished suite of poems. But, remember his long-suffering wife, Mathilde? Well, she certainly remembered the hell that Verlaine and Rimbaud had put her through and she would not go gently into that good night of her tormentors’ love story. When Verlaine, lent the manuscript, intending to set it to music, to her composer half-brother, Charles, she did a proverbial yoink and prevented Charles from returning Rimbaud’s work to her estranged husband or anyone who would even think of having it published. Upon divorcing Verlaine and remarrying, Mathilde gave up her hold on the manuscript, and after some further machinations, Verlaine had it published—naming it Illuminations, a subtitle Rimbaud had given it, meaning “colored plates”—in October of 1886.

Group portrait by by Henri Fantin-Latour, Verlaine (left) and Rimbaud (second to left)

Illuminations made Rimbaud a star, as he had always wanted and probably felt he deserved, but he would never know it. He had become a coffee trader in Harar, Ethiopia, when he developed bone cancer in his right knee. Rimbaud went back home to his mother’s farm one last time before dying on November 10, 1891, at age 37.

A rebel and an iconoclast till the very end, Arthur Rimbaud turned poetry on its ear, disrupted polite society on a whim, inspired the Surrealist movement in both art and literature, and gave generations of gay men a (if we’re being honest) completely unhealthy but nevertheless romantic ideal to turn to as an example of same-sex coupling that history has often tried to deny ever existed.

Oh, and he also gave us a pre-Titanic Leonardo DiCaprio in the otherwise unremarkable Total Eclipse, about Rimbaud’s and Verlaine’s relationship, if you want to experience an actual Season in Hell.*

*I’m only half-kidding...it’s not that bad.