To My Mother, on the 20th Anniversary of Her Death

Today marks the 20th anniversary of my mother’s funeral. It is also my 34th birthday. For 20 years these two events have been linked in my mind, such that a celebration of my life is also invariably a time to mourn my mother’s death. She died on November 2, 1999, after an all-too-brief battle with pneumonia.

Everything went so quickly, in little vignettes that would play out in my head forever: One moment she was suddenly sick, then she was sick in bed for two weeks, then she was at St. Francis Hospital, then they were rushing her down to Mt. Sinai in New York where we went to visit her—my brother, my aunt, and I. The doctors there said my mom had a 50-50 shot, and my brother said there was a chance she could die, but that didn’t mean anything to me.

I couldn’t quite fathom not having a mother. I had never had a father, but that didn’t seem to bother me much. He was only a man in a long-forgotten picture from my childhood, a distant voice calling from a distant land, my native Guyana—the first time he called, the first I ever spoke to him, was when I graduated from Clinton Elementary School. The second was when my mother died. She had never talked much about him, and aside from those two phone calls, he never made an effort to know me. So how could I miss someone who didn’t provide me anything to miss?

My mother, however, was all I knew. It was so often just the two of us; even though I had an older brother, he was 17 years my senior and only sporadically present in my life. Her birthday was exactly a week after mine—she would’ve been 76 on November 12—and as Scorpios we were more alike than I realized. Terse, very internal, prone to moodiness but every now and then filled to bursting with a joy, as Nina Simone once sang, that was hard to hide.

She wasn’t effusive in her love or her praise, but I always knew when she was proud of me. I think I knew she loved me. I don’t remember her ever saying it aloud to me, those three words: "I love you." I didn’t learn to say those words until after she died. Without my mother to anchor me to the rest of my family—my aunt and her family—they drifted into the background of my existence.

The funeral was the fifth of November… my 14th birthday. “Remember, remember the fifth of November," the old English poem goes, commemorating Guy Fawkes Day. But no one remembered, the events of the day weighing heavily on everyone’s mind. And it would’ve felt weird to be wished happiness on the occasion of my orphanhood. My brother would assume the role of my guardian, but he wasn’t ready for the responsibility of raising a teenager, and I resisted him the entire time until I was old enough to be on my own.

Instead, my friends helped finish the job my mother had started, the task of bringing me up. I had a truly motley crew of confidantes and accomplices waiting for me after I returned to school—still just the beginning of my freshman year—and my life returned to some semblance of normal. There was Krista and Gigi and Jenn and Paris and Jamie and Larry, most of whom I had known since my days at Clinton Elementary. Our numbers varied amid couplings and uncouplings, but shared drama and trauma drew us together the four remaining years of high school.

It was to them that I first came out—something I never got to do to my own mother, and the words remain unsaid to most of my other relatives—and these friends all accepted me without question or hesitation. When dinner was precarious, as it so often was, I could depend on finding a seat at any one of their tables. My friends first taught me how to say “I love you”—not just because we said it so freely with one another, but because they made me feel love as I had never known it before.

Krista and her mother Lauren essentially adopted me, absconding with me to Thanksgivings and Christmases in Connecticut with Krista’s grandparents, where I was welcomed as part of their family. The holidays became not the domain of my flesh and blood, but of the people who were there for me when I needed them. And who loved me as I needed them to do. This Thanksgiving is actually the first in more than 10, maybe 15 years that I won’t spend with Krista and Lauren now that we’re on opposite sides of the country. But even if I don’t see them or any of my high school crew for months or years at a time, I know that the familial love we experienced was crucial to all of us, whether or not we had our own individual families to go back to.

As for my relatives, I haven’t spoken to most of them since those first Thanksgivings in Connecticut. I felt let down for a number of reasons I can’t and won’t get into here… but I felt that when my mother died, they ceased being my family. At least in the truest sense of the word. Sure, there is our shared ancestry, shared genes, but those bonds are more superficial than anything else. Because they can so easily fade away.

As I’ve grown into myself, I’ve begun to learn about my own capacity for love—the enormity of it, and my discomfort and occasional inability to properly express it—and through that I think I’ve begun to understand my mother more. She cared for me, she took care of me, she put my needs before her own, more than I think I’ll ever know. That in itself is a form of love. It is, in some ways, a deeper kind of love than merely saying it. It’s easier than I thought to say “I love you,” but the actual act of loving, the sacrifice it requires—that’s the hard part.

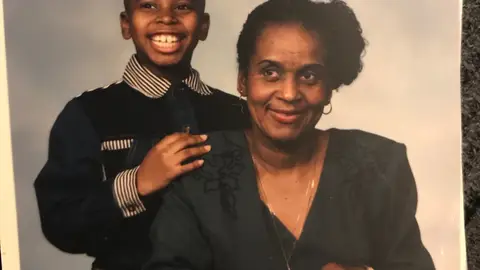

Main image: The author at age 8 with his mother.